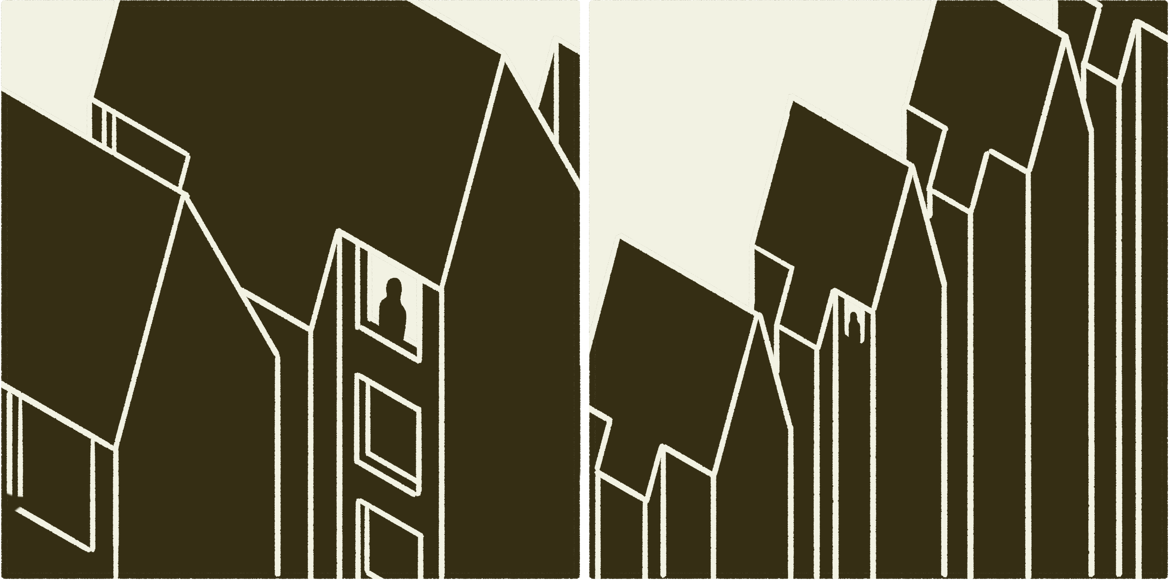

I live on the ugly side of a beautiful town by the sea on a pleasant plain where the black cliffs give way to sandy beaches. A huddle of red stone houses pepper the land between the sea and a ponderous conical hill.

A volcanic remnant. An igneous intrusion, etched by epochs, pocked with anthropogenic decoration, crowned with the jawbone of a blue whale.

And beyond that, on the south side, bathed in sun, flow gently rolling fields, crazed with valleys and rivers, hidden castles, ancient forests and tall tales, tracing steep paths up to the hostile moors.

The Lammermuir Hills, home to sheep and fugitives, heather, big skies and far horizons. A place to see beyond the confines of our little sorrows.

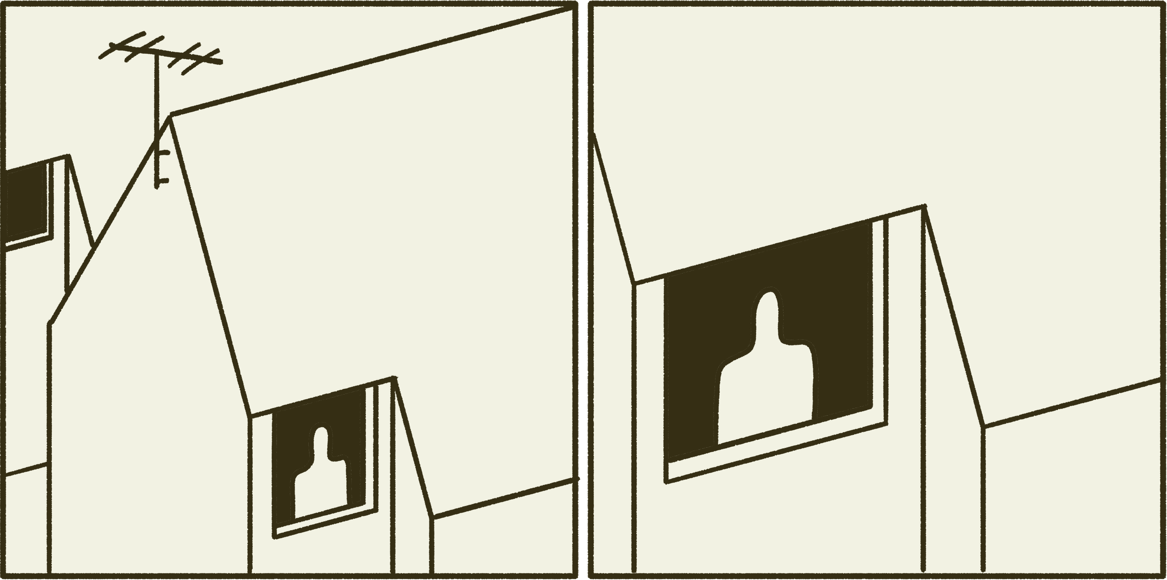

But, by necessity, I live in ‘the scheme’. A housing scheme, built in good faith in the 1960s by a government charged with providing for its people.

It is a noble scheme. A tidy, regimented row of identical grey units. Like teeth in the gears of a great machine.

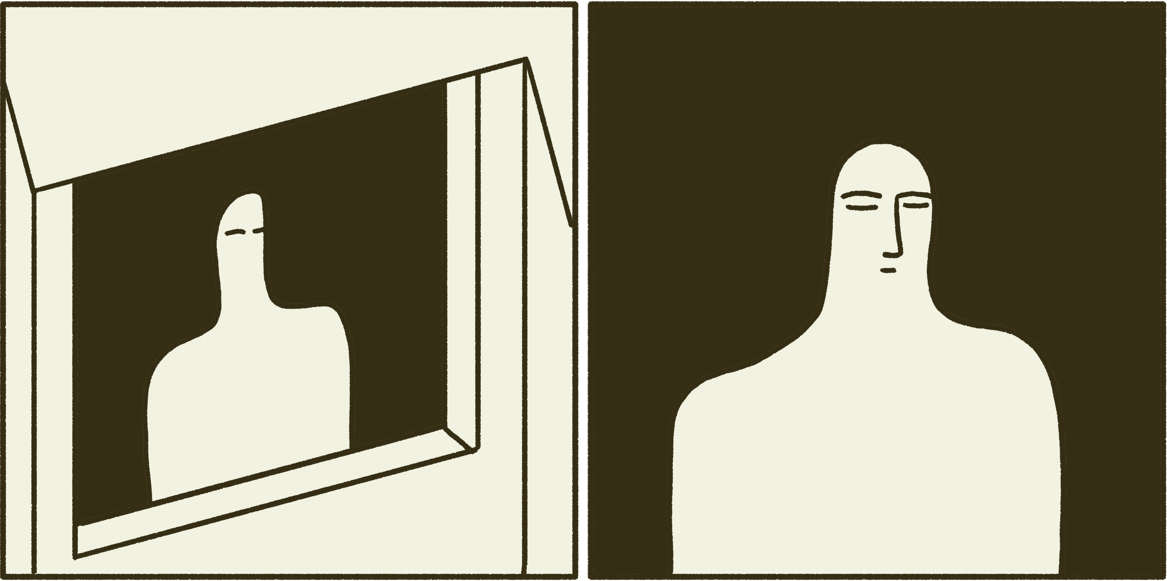

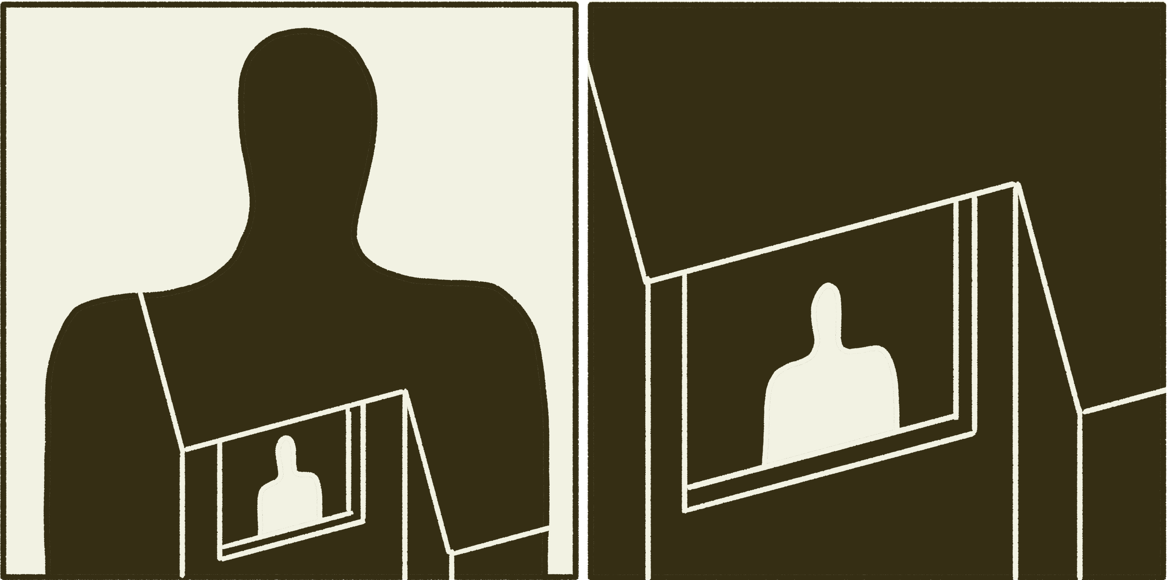

I’m ashamed that don’t feel its greatness. Instead, I am suffocated by it. To me, it is an architecture that disempowers by design.

A monotony that inspires acquiescence. Labyrinthine symmetry. No clear exit. No way out for the listless children kicking crisp bags into the wind.

Except for that ponderous hill looming in the morning, gleaming in the evening. I keep my head up, pointed to the hill. I take the long way to school with my daughter so we can stand at its feet for a moment.

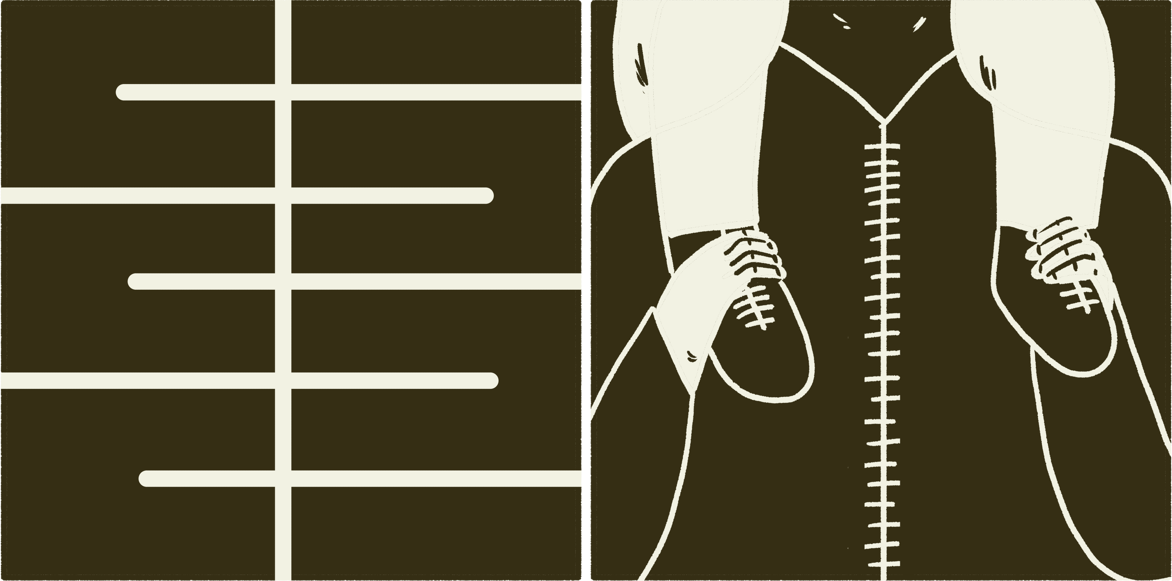

To remember the magic in my childhood. To teach her that the scheme is not as good as it gets. Because, like the trees on the hill, the child bends with the prevailing wind as she grows.

And I would rather she bends to the magnificence of the natural world than wither in the maze of a man-made scheme.