Trust your artist.

For the most part, my clients trust me. They trust that the illustration they commission from me will look and feel somewhat similar to all the illustrations that preceded it. In fact, I am sure they expect the illustration to look like it was made be me, in my own unique style. But expectation is a slippery emotion. Expectation can alter reality, bend space, ruin your holiday. Expectation is the reason Hogmanay 1999 was the worst on record. This is why, my first job as an illustrator is to manage the expectations of my client. It can make or break a working relationship. Most of the time, this is a very simple process. But sometimes, expectation blows up in my face. And I never expect it.

1. Style

There are many ways to manage the expectation of the client. The first and probably most important, is to have a portfolio with a consistent style. With a clear consistent style, the client will confidently assume that any artwork they commission will be in that style. It will look like it was done by that artist. This is perhaps the most obvious aspect of art in general. Name a famous artist, they have a style that springs to mind. Maybe they moved in and out of different styles for different periods of their life but the their style or styles are uniquely theirs. It is their brand recognition. And to be recognisable is the surest way to success as an artist (whatever that means). Well in this context it means, being memorable. Being memorable inspires confidence, it gets you more commissions, it sells more paintings.

But beyond just being commercially sensible, having a consistent and unique style is usually a sign that the artist has been doing what they do for a good wee while. It takes a long time to hone a style. It cannot be achieved by pretence. The conceit is obvious. Style comes on its own after years of doing. It is impossible to aim for your own style because in the beginning you have no idea where or what you are aiming for. There are some rare cases of artists who seem to emerge onto the scene with a preformed style. Appearing to be ready made. It is more than likely that they have been working on it since they were very young.

Most young artists will mimic their predecessors before they find their own rhythm. The results of mimicry can look great in the hands of talented people but ultimately it usually results in a fairly generic style, like you’ve seen it before. When the artist turns from mimicry to experimentation and amalgamates various styles and techniques, the art begins to take a unique form. Keep pushing that form and you end up with a unique style. It takes a while.

Strangely, much the same as you can recognise the adult in their childhood photographs, you can recognise the artist’s style peeping through in their early work, hidden amongst the unnecessary gloss. Almost as if it was always there, waiting to be teased out.

2. Communication

When I am asked to create an illustration for someone, usually we talk back and forth about the project, agree a price and develop the brief together. Then I spend a bit of time coming up with ideas and concepts according to the brief. As an illustrator, my favourite way to communicate these concepts is with pictures, unsurprisingly. These pictures are usually pretty rough sketches and they sometimes need a little bit of extra description to get the concept across.

This process is standard in the illustration industry. I learned this bit very early on at art college. Most illustrators will work like this in some shape or form. Rough sketch ideas to developed drafts to finished pieces. It allows a back and forth discussion between the commissioner and the artist. It is the backbone of what is essentially a collaborative piece of art. The degree of collaboration usually depends on the budget and the level of trust between each party; more money means more time to discuss the art, more faith means more creative freedom for the artist. Personally, I value creative freedom over money. But I do need to make a living so it’s a mixed bag.

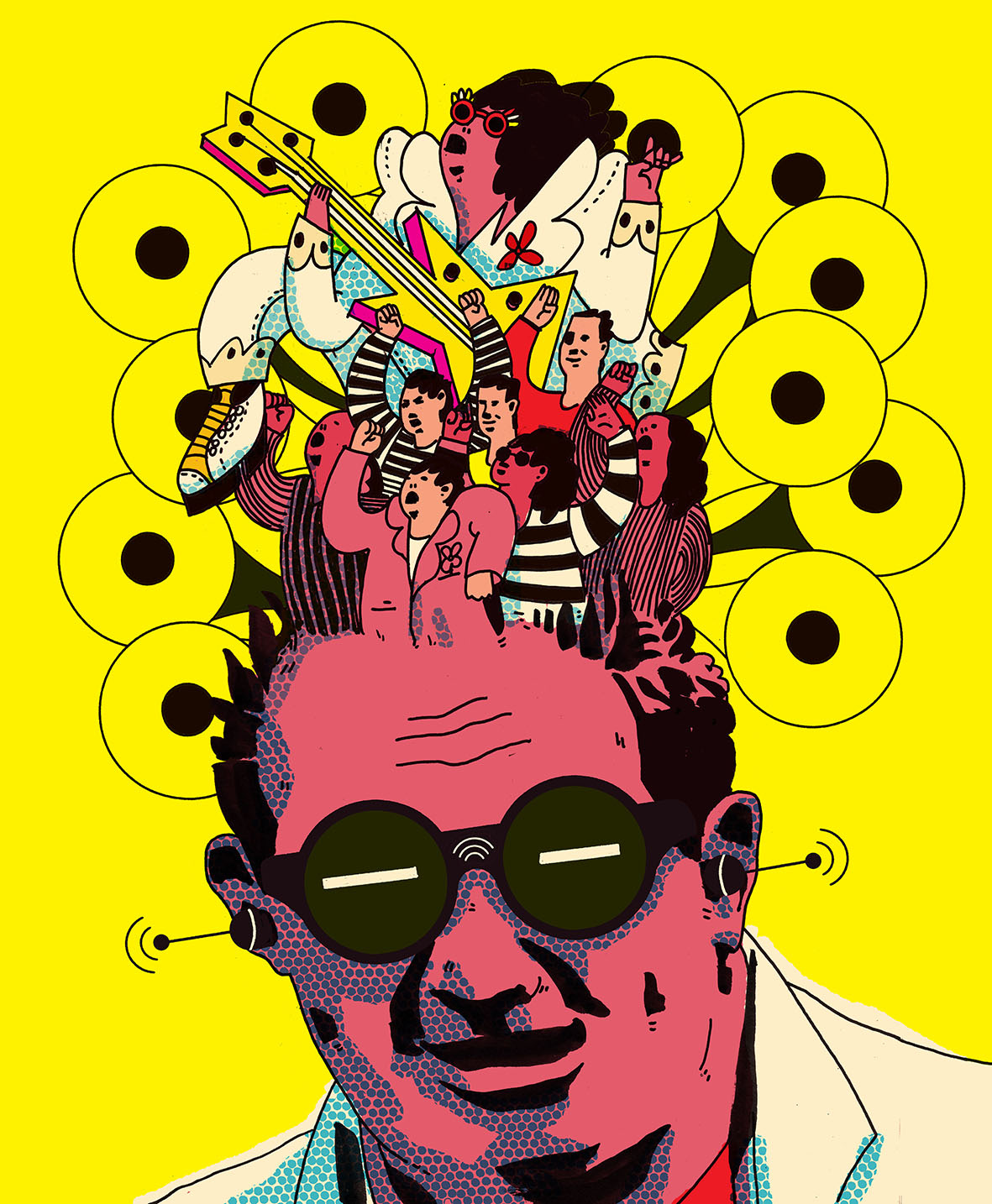

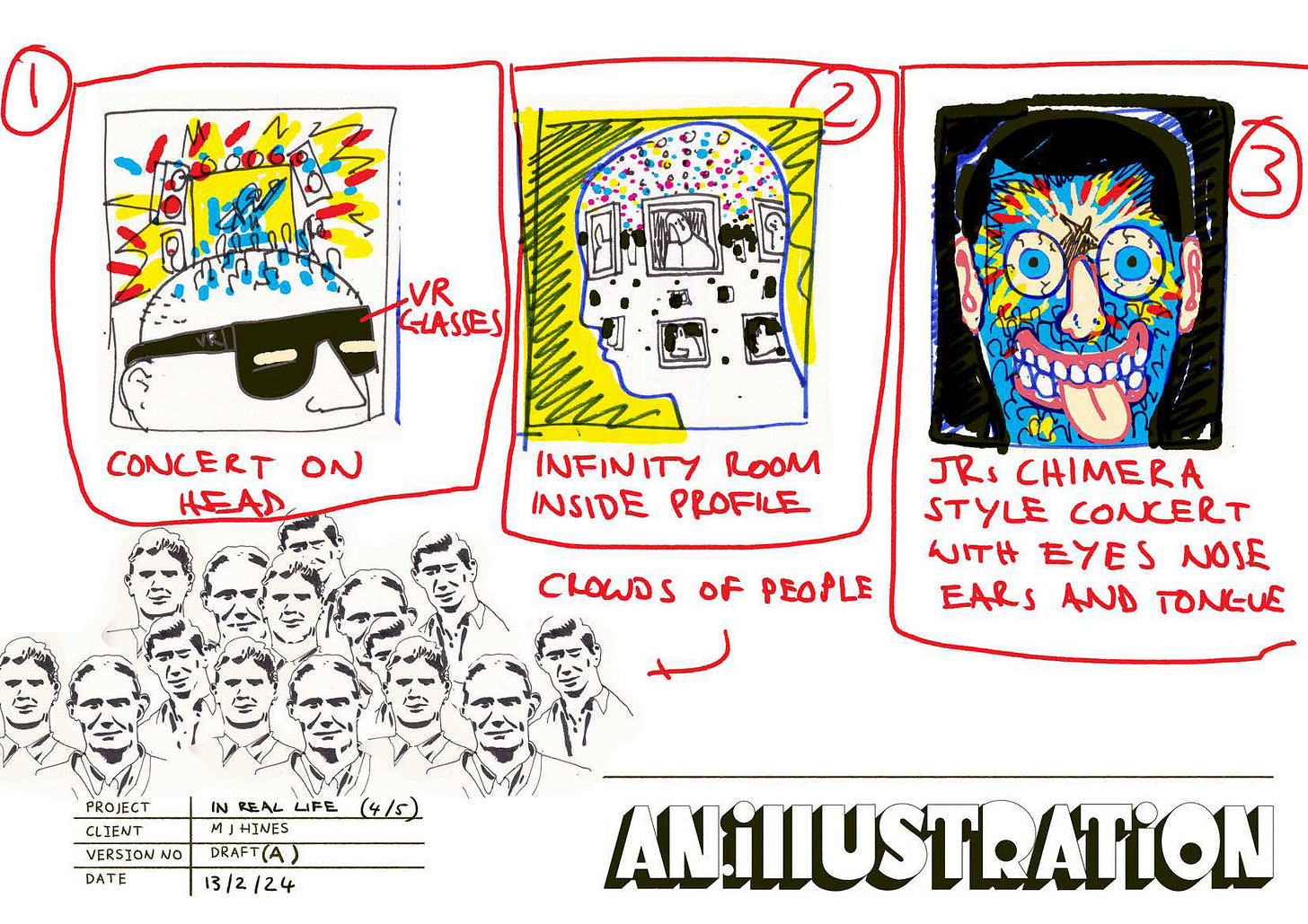

See the draft sheet below that I did for M J Hines at Fiction and Persuasion. These are the sketched concepts for the illustration at the top of this essay. The essay ‘The Experience Renaissance?’ is about the increasing sophistication of modern live events since the COVID19 pandemic. The three sketch concepts I gave him, directly reference different parts of the piece. Go read it after you’ve read this.

He picked concept (1) from this draft sheet and did not ask for any more explanation about it. He trusted me to produce something from this rough idea. As much as the final image looks completely different to the sketch, the concept is the same. On this occasion, the client accepted the finished illustration without any alteration. He liked it at first glance, which is a great feeling for me. I will only send out a finished piece if I like it myself. I don’t send out anything that I am not personally invested in. It might be emotionally unsustainable but that’s the truth. I don’t mind criticism, I can take it, I’m a professional, but I have to admit that when someone validates and trusts my artistic judgement without question, it feels good.

As a wee side note. This story may be apocryphal and I can’t even remember where I heard it, probably at art college. Quentin Blake when he was a young illustrator would send his rough sketches to the art director, get some feedback, then work on a carefully finished illustration. One day, an art director asked if he could use the first rough sketch instead of the finished illustration. And this became the Quentin Blake style that we all know and recognise today. An example of a style that happened organically. The young Quentin Blake didn’t know that this would be his style. But now it seems obvious.

3. Accept criticism

Rarely, and I mean very rarely, I get a surprise. The client doesn’t like it. It’s not what they expected. And I don’t understand. I am taken aback. The piece I sent is in my style and it matches the concept sketch that we agreed. What went wrong?

This has happened a handful of times and I am always perplexed. As a professional I must respond respectfully to dissatisfaction. I am, after all, being paid to create a piece of art for someone else. But I am not a robot. I am human. Anything I create is a piece of me. It means something to me. I take great pride in my work and the rejection breaks my pride. I know, it is a flaw on my part but there we are.

Most rejections are kind. Most people do not intend to hurt your feelings. They have their own priorities. They have their own shit to deal with. But sometimes, I get the odd comment which feels a little reckless. I once got a comment ‘you need to understand that hundreds of people will be looking at this every day and it needs to look good’. (I paraphrase but it was along those lines). To start, ‘Looks good’ is such an obtuse and vague statement, I really do not know what to make of it. Secondly, the inference is that my artwork does not ‘look good’. Like, oh yeah, I hadn’t thought about that. Seriously, this is not a constructive comment to make to an artist. And I have to admit I did not react well to it. Yes I had to suck it up. I had to be professional and respond to that comment constructively, but not before writing a few expletive replete draft emails which I promptly deleted.

This is not to say that I will not take criticism. In fact, sometimes I welcome it. If the illustration can be improved with outside input, then I’m all for it. But if I think the criticism will not improve the illustration or if I think the direction is not faithful to my style and vision, I will usually push back. This is because, every illustration I put out into the world reflects back on me. I care about each and every piece I send out. It is a part of me as much as it is a piece of commercial art. This is a good thing. If you are buying art from an illustrator, you should want them to feel deeply connected to it. This is what distinguishes commercial eye-stink from commercial artwork. If your illustrator pushes back against your suggestions, it is not because they do not care about your opinions, quite the opposite, I guarantee if they are a good illustrator, they will think very carefully about your suggestion and they push back only because they do not think it will serve the project and the art. It is a difficult thing to do. They need the money after all and pushing back against a client risks losing the commission. If they push back, it is usually for a very good reason.

I have found that experienced designers and art directors tend not to make suggestions that undermine my style. But then, they have spent their careers honing their own expectations of what an illustrator will produce and how to communicate that expectation. Criticism from art directors is usually very constructive. They offer solutions and suggestions to the aspects of the illustration they think do not work. They sandwich these suggestions between what they like about the work. I believe this is called a shit sandwich. It works. Art directors are also less emotionally involved than, say, an individual blogger or owner of a company. This allows them to remain distant from the criticism and their communication style reflects this. It is clear, considered and they avoid emotive language.

Understandably, small business owners and individual bloggers are more emotionally invested in the art that I create for them. The illustration I create will represent their brand, their identity, and it has to look good. It is my job therefor to communicate the process as well as I can. This means that I have to be the art director and illustrator in one person. I split myself in two and act as broker between ‘me the illustrator’ and the client. Doing this has allowed me to distance myself from criticism and instead of getting upset, I am better able to understand my client’s concerns. Which gets to the rub. The point of this rambling essay.

The weird psychology of expectation

Hogmanay (new year’s eve) 1999 was the worst on record, for me. Hogmanay in Edinburgh is a big deal. On the the 31st December 1999 I was nineteen years old. I was studying illustration at Edinburgh College of Art. The city was throbbing with anticipation. There was a palpable buzz, a gathering storm in the days preceding it. At 6pm on the night they lock the gates to the city centre. You need to pay to get in, but if you know the right people you can get smuggled in for free. There are whispers of secret parties, loop holes, falsified documents, underground tunnels, basements that open into the centre of the fray. And talk too of who is who and who is going where with what at what time. It’s overwhelming. And that fucking song! Tonight were going to party like its… blah blah blah.

I don’t like parties, but I didn’t know that at the time. I just thought I was flawed in some way. I thought there must be something wrong with me because everyone else seemed to enjoy parties. I found certain adulterants that made parties bearable however. It all added up to this muddle of anticipation, excitement and gut wrenching fear. My expectations of the night were off the charts. But the prospect of some transcendental life changing moment descended into one of the dullest evenings of my life.

We didn’t get invited to the secret party. We couldn’t break in to the centre of the city. We wondered around listless and bored in empty streets. The distant noise of the biggest party in the world beyond our reach. My friend got into a fight with a petrol station attendant. It was sad. Bleak. And I ended up on the floor of some stinky student flat. All this despite the fact that my mum’s flat was in the centre of town. I chose not to stay at my mum’s place because well, you know, it was my mum’s place. They had a great time, apparently.

The next year, I did not expect much at all. Yes that’s right, I had a fucking wonderful time. Different friends, got into the centre, danced a lot, got just the right level of high, got a lift home, slept in a comfy bed, woke up feeling good, ish.

I think this is what happens when someone is disappointed by a finished illustration. Their expectations cannot be realised and disappointment is inevitable. I assume when someone finds my work, it is mostly by chance. They stumble upon it online and it strikes them. They were not expecting anything. Quite often I’m sure they weren’t even looking for an illustrator when they see my work. They just see it and it strikes a chord in some way. But the moment they wonder about commissioning a piece from me, that’s when the expectation sets in. Then they are no longer about to stumble upon a piece of art, they are anticipating it.

So, if you would like to commission an illustration from me or any other illustrator, remember to put your expectations to one side. Put your vision away for a moment and accept the art that is presented to you as if you just stumbled upon it. Remember why you liked their work in the first place. It was their work and style which drew you in. That is the point of employing an artist to make art for you. They have the vision. They have spent years honing that vision and they know what they are doing. Trust them and you will be rewarded with a great piece of art. Or don’t and just get AI to do it. You can poke it and prod it until it gives you what you want, and it wont get upset with you.

I must stress that my customers are very rarely dissatisfied and whenever this has happened we have always been able to get to an agreeable solution so that we both go away satisfied. It just takes a wee bit of care and understanding. To anyone reading this who has paid me money to make art for you, I love you. Thank you.

On that note. I am open for commissions.

Many actual scribes would not be able to phrase it better. Looks like we’re in trouble.

I thoroughly enjoyed collaborating with you, Alexander. I love your voice and style, and your imagination to take an abstract idea and put it on paper.